Maxwell Sather (Gen Z), Zoe Sather (Gen Z), Nicole Walker (Gen X)

*

Abstract: TikTok is a media platform devoted primarily to social media users age 10 to 20. These users appreciate and are able to digest short-form films delivered to these adopters in 15, 30, and 60 second intervals. TikTok uses algorithms similar to older models of social media such as Twitter and Facebook. As the user ‘likes’ (by pressing an electronic button shaped as a heart) a video, follows a particular TikTokker, or searches for content by category, the algorithm then ‘pushes’ content that the user will fine diverting, amusing, or distracting. There is some evidence that how long one lingers on a TikTok video contributes to the algorithmic calculations but to an independent observer, this is difficult to verifier. Because a considerable number of TikTokkers are comprised of the Generation “Z”, our work here is to determine whether it is possible for a person of the Generation “X” to develop a TikTok strategy, or, algorithms willing, a following, without be called a “Boomer” by other participants.

Keywords: Tik. Tok. Upload. Seconds. Chicken.

Introduction

In an effort to promote Walker et al’s essay collection Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster, which was released in March 2021 in the middle of a pandemic, Walker undertook an unconventional approach. While promotional plans had including serving charcuterie at various book-selling events, Covid 19 et al., prohibited the leaving of house, the sharing of food, and the selling of books. In 2022, Walker endeavored to produce several short videos and upload them to a new social media platform with the help of Sather et al. whose experience, attention span, and training prepared them especially for this work.

Methods

Study Design: TikTok was selected as the platform for a dyad of reasons. 1. Subscribers to older model social media conglomerates like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram had been previously inundated with attempts by Walker et al to entice them to read her collection, contaminating those platforms. 2. TikTok affords its users a companionable hashtag system, where different “tiks” can be sorted by “toks.” Thus, #Booktok proved the fecund yet unsullied ground by which we could conduct our experiment.

Sather et al’s paternal parent is a filmmaker which is distinctly not the kind of video Walker intended to produce. Sather et al had both made TikToks with varying degrees of “likes” or “followers,” making them the ideal cinematographers for this study. Materials used included an iPhone 11, a frying pan, a refrigerator, boneless, skinless, chicken thighs, bacon, square-shaped Tupperware, and a copy of Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster. While each videos strategies differed slightly, we adopted the ‘common’ form of video collecting, pointing the camera at the subject and engaging the ‘record’ electronic button.

In preparation for the procedure, Walker first decided what would cook for dinner. Second, she found a passage in Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster (the title of send book she has currently converted to Macro FN 32) that paralleled that particular meal.

Limited resources, in both imagination and product, constrained the choice of specimen primarily to chicken. Cinematographer Sather positioned the camera implement of his handheld device toward Walker as she unwrapped boneless, skinless chicken thighs from the Foster Farms cage-free brand of chicken. In an attempt to preserve the integrity of the process, chickens raised in crowded but uncaged growth vessels determined our purchasing options. Once the chicken has been removed from the packaging and placed between layers of parchment paper, concern for the welfare of the chicken no longer limited the parameters of the experiment. In order for the chicken thighs to ‘cook’ evenly, thighs must be pounded flat. Sather et al recorded the flattening by aiming the camera implement from the handheld device toward Walker’s cutting board and rolling pin, thereby recording the process of pounding the meat into squares. Walker then laid the chicken thighs in an admixture of flour, paprika, celery salt, and garlic powder, covering both sides evenly, then lying flat in a beaten egg preparation, then again laid into bread crumb coating, designated “Panko.”

Here, the visual recording was halted and the audio recording commenced. Sather et al attempted to instruct Walker on the technological steps to implement an audio recording but gave up and recorded Walker as Walker read Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster:

I laid the chicken between wax paper and got out the rolling pin.

“Where’s the pizza?” she asked. She was used to rolling out pizza dough with me.

I showed her the chicken thighs and pointed out how fat and uneven they were.

“We’ve got to pound them thin,” I told her. “For chicken tenders, they need to be half an inch thick. Do you want to try?” She said yes but she hit the thighs with no force at all. “You have to hit them hard.” I took the rolling pin from her and gave them a whack. They submitted, flattening out, becoming more dough than flesh.

In the middle of the next swing, Zoë yelled for me to stop. “That hurts the chicken.”

I understood her point. It was an odd thing to do: take these round thighs and make them flat. Chickens, factory-farmed grow so fat and thick, the chickens can’t walk. It’s ridiculous, I thought, as I continued to pound the yellow flesh into smooth medallions, that the chicken-growers spent so much time, energy, and DNA manipulation making their chickens grow unnaturally fat and here I am, just thinning them out again. But that’s the only way I knew how to make chicken tenders.

This procedure began as with Experiment one, with the packaging of the specimen: Walker unwrapping butter as she prepared potatoes for Thanksgiving. Given time limitations, Sather et al. cooked, read, promoted Macro FN 32 and conducted recordings simultaneously. It should be noted the Joel Robuchon suggests one pound of butter for two pounds of potatoes but not even Walker has been able to repeat this experiment without severe damage to both the lab, the specimen, and the personnel. However, these potatoes, peeled, quarter pound buttered, quarter cup milked, and whipped in the culinary centrifuge, turned out as expected: buttery but not disastrously so. The results of the promotional aspect of the experiment are less certain.

Results:

For the third experiment, due again to time limitations and the labile conditions of the specimen, Sather et al recorded cleaning the refrigerator instead of focusing on a singular aspect of a specimen such as chicken or butter as in experiment one and two. The cinematographer recorded Walker removing squares of Tupperware, petri dishes of microorganisms, and hazardous biologic material from the specimen for a 30 second interval and then recorded restocking the specimen with material inoculated with spores and microbes in conditions not yet catalyzed for spontaneous growth.

Walker, still restricted in audio capacity, required Sather et all to adjust the technology for Walker to read from Macro FN 32:

I spill applesauce down my shirt while trying to shape it into something palatable for Zoë. This little baby will not eat. Or, she won’t eat anything as perimeter-defying as applesauce. She will not eat anything that isn’t square, so I’m always sticking macaroni and cheese into the refrigerator in a Rubbermaid container. When it’s cold and hardened, I pop it out of the plastic and cut the newly formed mass into squares. Everything must be made square—because she likes the pointy edges or because I am limited to squares by my sculpting skills, I’m not sure. Mashed potatoes I take between my hands, pat into a square, and fry. Cucumbers, cut down the middle, edged, and quartered, she’ll eat. It looks strangest on the meats—chicken squares, steak squares. I try to resist taking her to Wendy’s daily for the pre-squared hamburgers. If you take the tops and bottoms off Wendy’s fries, they are practically Pythagorean.

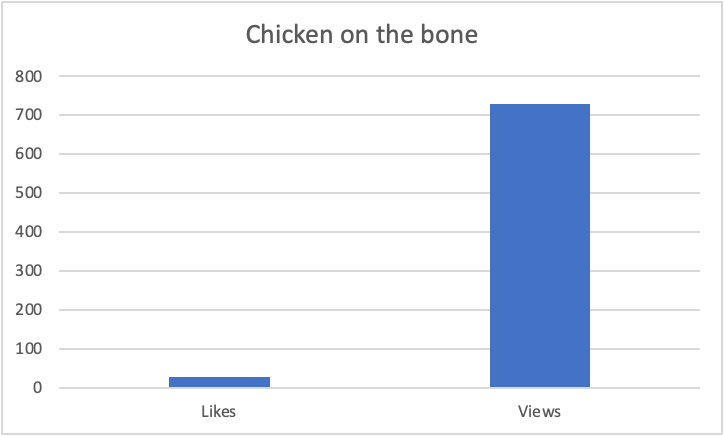

Because the specimen chicken has been well-studied herein and bone-in chicken may disturb our reader, the editors request Experiment four only be charted and cited. However, please note, Sather et al. coats the chicken in paprika, celery salt, and garlic powder in the data-collection.

There is chicken on the bone. There is chicken off the bone. Chicken on the bone is the chicken I’d want in all its decadent renderings—by all I mean one. Fried chicken. There are many bone-in chicken recipes like chicken hindquarters in port and cream, barbecued chicken, buffalo wings, though they may be a kind of fried. But fried chicken is a testament to the beauty of the disarticulated chicken. Every piece a handhold. Every piece its own integrity. The coating wraps a thigh like snow, a breast like a scarf, a leg like a stocking to protect it from the cruel world of hot oil. Frying chicken is the nicest thing you can do to a dead chicken.

But there are some who cannot eat the chicken on the bone. Breast of chicken, boneless thighs, cubed in korma, rolled cordon bleu, that’s doable. At the bar, spicy drummette in my right hand, hot sauce on my cheek, a pile of bones in front of me, I turn to my friend Ander, who will not eat the boney chicken but is currently eating chicken tenders. I do not comprehend his reluctance.

“It’s the same thing,” I argue.

“It’s not.” He pushes my plate of sticky bones further away.

“But you eat meat. Chicken. Steak,” I say.

“I prefer hamburger,” he says.

Perhaps he does not like the resistance of muscle.

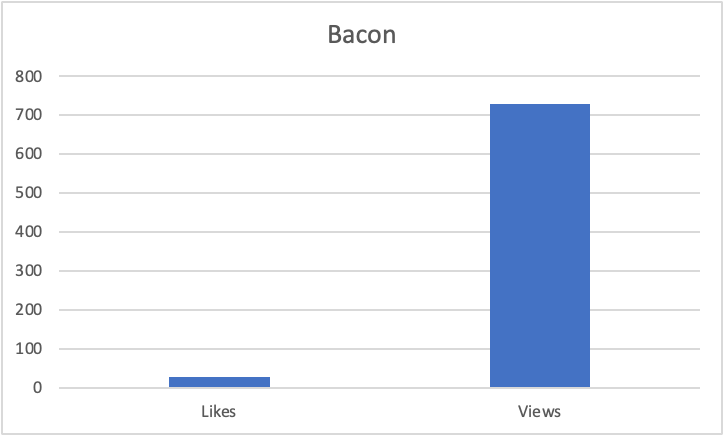

A final experiment, henceforth referred to as Experiment five, produced outlying results. While the primary visual record is of the specimen frying in a pan, inferences may be made that specimen bacon, while equally subjected to unseemly living and death situations, is easier to render digestible because of its exuberant effect on the tastebuds, even as perceived through a visual medium. The data here thus outlie our previous experiments but are noted for significance. Please note that while the inputs trend higher, the ratio remains the same. Sather et al include these data for reference only.

During the H1N1 pandemic scare, I start stockpiling groceries. I buy twelve cans of Cento tomatoes, twenty boxes of spaghetti. It’s not as if I think the grocery stores are going to close tomorrow. But I should start preparing—part as pure logic and part as an offering to the gods of swine flu. I buy two pork tenderloins, two pounds of bacon, and a saver-pak of pork chops. A little protein in the form of cheese won’t save me but a lot of pig might. I’ll fight fire with fire. I’ll develop my own antibodies to the H1N1 out of bacon. I realize that it’s not the pig that will kill me, but, lacking any other sort of game plan, I reason that pig is a prophylactic. I will eat him homeopathically.

In conclusion, it shall be inferred that TikTok, while a forum designed for a generation well-practiced in giving short-term attention and incessant dopamine infusions, other generations may learn to adapt and avoid being called “Boomers” if collaboration with the generation Z may be forced. However, we must conclude that becoming a TikTok sensation is not likely. These experiments must be repeated for results to prove valid. Future study is indicated in the specimens of pomegranate, beef tongue, and beef Jell-o. The larger conclusions may be even less promising. Self-promotion is an embarrassing sport and the promise of finding book readers in a TikTok world is ever shrinking. And yet, the show must go on.

Notes: Walker neglected to push “post” on Experiment one so Experiment one should now be imagined as Experiment five. Walker also included two additional hashtags: #food and #chickentenders which garnered, we believe, more views. It also drew three comments: “Is this a book? It seems like a book.” And “Thanks for the dating advice, coach” and “This seems like an audiobook.” And “You should write a book.” These comments seem linked to the fact that Walker neglected to record an image of Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster. Walker’s Macro usage has been suspended until further investigations can be conducted.

Chart for Experiment One updated as of 12/17/2022, 11:05 a.m.:

*

NICOLE WALKER is the author of Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh and Navigating Disaster, (AKA Macro 32) The After-Normal: Brief, Alphabetical Essays on a Changing Planet, Sustainability: A Love Story, Where the Tiny Things Are, Egg, Micrograms, and Quench Your Thirst with Salt. You can find her at https://www.facebook.com/nicole.walker.18041 Twitter: @nikwalkotter and website: nikwalk.com and TikTok @nicolewalker263

No comments:

Post a Comment