Sunday, December 25, 2022

Dec 25: Merry Christmas & an Invitation to Send Us Your Reading Recs

Saturday, December 24, 2022

Advent 2022, Dec 24, Dave Griffith, Station X: Christmas Eve, Strawtowne Pike, Bunker Hill, IN

Author’s note: “Station X” is part of a 14-part collaborative text and audio project between myself and printmaker and musician, Kyle Peets, that reflects upon daily life during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Though the project is not explicitly religious, it does borrow the narrative structure from the popular Lenten ritual the Stations of the Cross or Way of the Cross, in which pilgrims reenact the Passion of Jesus Christ by processing and praying before tableaux depicting different moments from that story.

The text and accompanying ambient music were composed independently of one another during the pandemic at a distance of over 2,000 miles—me in Indiana and Kyle in Oregon. Kyle did not have access to the text I was writing while he composed, and I did not have access to the music he was composing while writing. This was to ensure that any synchronicities would be accidental.

We suggest reading the piece, then listening to the recording.

That was at the new house.

At the old house on Stratowne Pike, the house my grandparents and my two aunts moved into when my grandfather was diagnosed with cancer, we would walk out past the barn, across the barren field toward a dark windbreak. It was farther than it looked, and colder out there in the middle of the field than it was close to the house, and so we always bundled ourselves in hats and scarves before beginning the walk out to the wood.

My dad would carry my brother on his shoulders at least part of the way. My uncles would be carrying cans of beer, which they plucked from the case cooling on the back porch. Out there in the woods there wasn’t much to see, really, except some rusted farm equipment, old beer cans, maybe a whiskey bottle. On the walk, my dad had a knack for finding arrowheads just sitting on top of a furrow, turned up when the field was plowed under.

This is the house where we gathered for many Christmases and Thanksgivings, where we would play heated games of Trivial Pursuit and Pictionary, and then stay up late giving dramatic readings from the Collected Poems of James Whitcomb Riley, the so-called Hoosier Poet, whose 1885 poem “Little Orphant Annie” inspired the creation, years later, of the comic strip.

Little Orphant Annie's come to our house to stay,In my memory, the poem took the place of “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” in our Christmas Eve ritual.

An' wash the cups an' saucers up, an' brush the crumbs away,

An' shoo the chickens off the porch, an' dust the hearth, an' sweep,

An' make the fire, an' bake the bread, an' earn her board-an'-keep;

An' all us other childern, when the supper things is done,

We set around the kitchen fire an' has the mostest fun

A-list'nin' to the witch-tales 'at Annie tells about,

An' the Gobble-uns 'at gits you

Ef you

Don't

Watch

Out!

But that house is gone now. Four years ago, a tornado blew through the county and came near enough to nudge the house off its foundation. House inspectors came and judged that it was no longer a safe place to live, so it was condemned and razed. All that is left is the gravel drive with its strip of grass and weeds down the middle, and a faint outline of where the foundation had been.

Sometimes when I am driving back from Indianapolis, after a weekend with my kids, I make a quick detour off route 31 and visit the empty lot, remembering the feeling of anticipation I felt as the house came into sight; how the dogs would begin to bark and rush out to our van to greet us, followed by my uncles who would come out to ask if they could help carry luggage; how I would hug them, or, as I got older, shake hands; how as we all walked into the house my uncles would grab beers from cases chilling on the porch, and, later, as I got older, I would grab one, too.

In the Google satellite images, images taken from the USDA’s Farm Service Agency map data, the shape of the gravel drive is still clearly visible; the way that it ran parallel to the north side of the house and then made a loop around the garage and then met back up with the drive again. When you zoom in to several hundred feet from the ground it looks like the looped rope of a snare.

But when you drag the small icon of a person over the old gray asphalt, it glows blue, meaning that a Google car has driven past. I drag the little orange person over the green fields, my cursor holding them by one arm, their legs dangling and swinging with the sudden motion, like someone being carried away by a clutch of balloons, and drop them on the blue road in front of the driveway. It is then that the house appears. There it is: the white gable of the roof is peeking from behind a line of trees in full leaf. Orange daylilies flank the entrance to the drive.

According to the timestamp at the bottom of the screen, it is June of 2009. It is a glorious day. The sky is a wash of light blue at the horizon that grows more and more intense and saturated with elevation. Among the white puffs of clouds it is deep robin’s egg, and with a dragging of the mouse upward I can see that the sun is white and blurry at its nadir and beyond the sun it is Marian.

It must be early June because the corn in the adjacent fields has just emerged, several inches high.

If I close my eyes, I can feel the heat of that sun and smell the odor of those lilies.

A few seconds of meditation and I am there walking that drive way; the noise of my shoes on the gravel like a needle traveling the groove of a record.

Dave Griffith is the author of A Good War is Hard to Find: The Art of Violence in America (Soft Skull Press). His essays and reviews have appeared in print and online at the Paris Review, The Normal School, Another Chicago Magazine, The Los Angeles Review of Books, the Utne Reader, Killing the Buddha, and Image, among others.

Kyle Peets is a multi-disciplinary artist and educator who has exhibited his work nationally and abroad. He has had solo exhibitions at Platte Forum gallery (Denver, CO) as well as various group exhibitions: Character Profile at Root Division gallery (San Francisco, CA), Art Is Our Last Hope at The Phoenix Art Museum (Phoenix, AZ), and Art Shanty on the frozen White Bear Lake (Minneapolis, MN). His work has been published in the periodical SPRTS by Endless Editions (New York, NY), and is archived in the Watson Library Special Collections, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and MoMA Manhattan. He received his MFA in Printmaking from the University of Iowa and a graduate certificate in Book Arts from the Iowa Center For The Book.

Friday, December 23, 2022

Advent 2022, Dec 23, Jenny Spinner, Um Aidan

I remember that iris, a dome of florets now more gray than blue, not solid but patterned, with bits of white breaking through the way light spills from the bottom slit of a closed door. Back then, we spent hours holding each other’s gaze, locked in study and reassurance: I’m here. You’re here. Once, while changing him in an airport bathroom—he was about six months old—a woman leaned in, interrupting us. She put a wrinkled hand on my arm, and said, “I remember that, too. Don’t blink.”

But I did blink, inevitably, and now he’s more man than boy, elbows propped on an aluminum-topped table, sweatshirt sleeves pushed back, popping small balls of falafel into his mouth. He brought me here because he knew I’d love it—your kind of food, Mom—and I realize he finally knows me the way I know my own mother. Which means he knows only what he can bear to know. We’re at a hole-in-the-wall falafel joint tucked into a covered alley off a busy street in Wasat al-Balad. He orders foul and hummus and mouttabal. Someone slaps two round discs of bread on the table. There’s no menu, but my firstborn knows what he’s doing.

In the last few days, we’ve shared more words than we have since he was a child. He tells me about his visit to Palestine, the differences between Moroccan and Iraqi dialects, the Circassians who guard the royal family, and that time he inadvertently walked into the quiet room in the library and forty pairs of eyes lifted to stare at him, not hostile, just looking. When the man at the market across from the university gate asks why he is studying Arabic, he says “because I love the culture” not “politics.” He leads me inside: When the fruit comes out, it’s time to leave. Women sit in the back of the cab, not the front. We talk about the crazy traffic in Amman and the constant honking, and then he remembers that time he drove home to Philadelphia from the shore and a violent thunderstorm flooded the roads and he couldn’t see at all and he was terrified. He’d only had his license for six weeks, and he didn’t want to be in charge anymore. He wanted to give it all back, but he couldn’t, so he pulled into a mall parking lot to wait it out, only to have an unsympathetic guard insist he keep moving. It’s happened to him twice, he tells me, when he’s been on the road and it’s so dangerous that he can’t see and the only thing he can do is white-knuckle the wheel and makes all sorts of promises to himself and to God if only he survives. You know that feeling? he asks me.

Just that morning, after the latest test results arrived in my inbox—the doctor can’t reach me here but the tests can—I’d sunk into a heap on the chair in the corner of my hotel room. The doom in my stomach rose to my throat, and I swallowed hard, trying to breathe. By the time we met up later in the day, I had decided I wasn’t going to tell him, but then I did, a little, enough. His eyes met mine for about five seconds too long. Those eyes. I’m here. You’re here. I’m still here.

Sometimes it’s hard to reconcile this man of mine with the boy who was so shy as a child that he couldn’t look anyone in the eye. At his first soccer game, when he was five, he sat on the sidelines and cried because he was too afraid. For so long, he clung to me like a shadow. But now, here he is, leading me all over this city, ordering my tea, hailing cabs, rifling through my wallet for the right bills, shooing off hagglers, translating for his host family. When we cross the street, I tuck into his side, watching not the traffic but his feet. When he moves, I move.

But I’m always a step behind these days, anxiety saddled to my waist, weighing me down as I try to keep up. At home, in the old life, I am the professor. Here I am the student. More than that, here I am Um Aidan. We’re climbing the steep road near his house as the sun sets in a pink splendor over the sandstone buildings dotting the hill. He’s telling me about Naji al-Ali’s Handala and the men who run coffee out to your car on silver trays and the dried miramia leaves his host mother will crumble into my tea, promising to cure me of any ails. Keep going, I want to say, my voice cracking with love and pride as he strides ahead with a confidence I’ve never had. My boy. Keep going and do not look back.

Jenny Spinner is a professor of English at Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia where she teaches creative nonfiction and journalism. She received her MA and PhD in English from the University of Connecticut and her MFA in Nonfiction Writing from Penn State University. She is the author of Of Women and the Essay: An Anthology from 1600 to 2000 (U of Georgia P, 2018).

Thursday, December 22, 2022

Advent 2022, Dec 22, Ander Monson on the Pleasures of a Book all about Road House

Pain Might Actually Hurt?:

on Sean T. Collins's Pain Don't Hurt

Ander Monson

*

1. On the spectrum of bad ideas for books, watching the Patrick Swayze movie Road House repeatedly and writing an essay a day about it for a whole year, 365 days straight, has to rank pretty high. My friend Sean (not T. Collins) once went to his parents’ cabin when they weren’t there, he told me, and took one of every pill he found just to see what would happen. That was not a good idea, but it's one with a relatively limited half-life, unless they were into some really weird shit. I remember he said he just got bad diarrhea, which is about as positive as an outcome as one could imagine. But an essay a day—for a year—about Road House is a lot.

2. To be fair I recently watched another movie 146 times and wrote a book about it, so I know what I’m talking about when I tell you this isn’t a great idea. I did write about Predator every day for a year, but I didn’t write an essay a day. I suppose, in retrospect, I could have.

3. I also haven’t, to tell the truth, yet finished the Road House book, which is Pain Don’t Hurt by Sean T. Collins: As of this writing I’m only on essay 121. It’s not a book you can just blow through, unlike Road House the movie which is very easy to blow through, though I have watched it, as of right now, in the middle of this sentence where I am meeting you, exactly once. I’m not quite sure how I missed it, having watched pretty much every other action movie of the 80s a lot, often on repeat. But I realized while writing Predator that of all the 80s action movies I’d never actually seen Road House, and neither had my wife. So we watched it last year.

4. It's a lot! It makes so many kinds of sense that it makes none. Road House is not a consistent piece of art except in its inconsistency. It’s a light, weird action movie that coasts along on a truly bizarre premise and the irresistible hotness of Patrick Swayze but by the end turns for no real reason into a brutal murderfest. The tone of the movie veers wildly and unexpectedly from wacky sexy zen to dark af for no reason I could discern. Little of the plot makes any sense, starting with its initial premise in which there is a world where you might hope to attract and pay nationally-known celebrity bouncers six figures (in 1980s money!) to clean up your shitty local bar. Things devolve from there. Few of the movie’s lines of dialogue hold together when you look at them for more than a few seconds (which Collins directs our attention to many times, for instance the classic line "Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick?," uttered in the mode of a question like "Is the Pope Catholic," yet the answer, very obviously, is no; stuff like this happens a lot in the movie). If you would like a smart writer riffing on—not just bagging on—a kind of dumb movie, then you'll like this book a lot.

5. What drives any of us to our subjects? I watched it, thought it fun and forgettable, and filed it away. For Sean T. Collins, however, it became an animating force. A whetstone for the mind. An idea that was so crazy it just might work.

6. It does work. It works great.

7. So you actually don’t have to buy Pain Don’t Hurt to read the essays, but you should if you can find a copy. It goes in and out of print, I guess, maybe because all 365 essays are available on his website under the tag ROADHOUSE. The blog versions have one major advantage, which is that they include screenshots from the movie to illustrate his points. This is useful if you haven’t seen the movie at all, or, like me only once, or can’t call to mind all the minor and often throwaway characters in the film, nearly every one of whom gets a deep treatment, or just don’t want to rewatch the movie to refresh yourself of all of its nuances.

8. The primary disadvantage of reading them onscreen is that the project really is a book; it reads better that way, as something you can hold in your lap and that has all the authority of bookness to it and all of the weird uneven sexiness of Road House. This is a source of great friction between the authority of the artifact and the dumb idea and subject matter of the book.

9.There are a lot of good introductions to Road House and why anyone might care about Road House in this book, but my favorite so far is in 107, “Dalton’s Back,” a tight little essay about just that, the spectacle of Dalton’s sexy back:

Road House, when appreciated properly, is less a film than an ecosystem: hyper-efficient, factory made late-‘80s star vehicle; barely competent, incoherent MST3K fodder; rock-solid action flick; obvious, excessive homoerotica; smarter than it looks; dumber than it realizes; a Ben Gazzara film; a Terry Funk film. When you watch Dalton’s flawless, godlike arms, traps and shoulder blades flex and contract in harmony, you’re watching the character and the movie in metonymy. You’re watching a real physical thing—Patrick Swayze’s beautiful, beautiful body—do what Patrick Swayze’s character and Patrick Swayze’s movie are also doing. As below, so above.

10. The movement here is obviously the real show. And like many iterative projects over a sustained period of time, the life of the writer often sweeps into the project in big and obvious ways, as it does in 53, “Why We Fight,” which is also another great introduction to ways of experiencing Road House:

'This has been, without question, one of the worst weeks of my life, but one man offers succor.’” / I tweeted this as I sat down to write today’s Road House essay. I knew exactly what I was going to write about: I knew the scene, knew the moment, knew the angle, knew how to flesh it out. It’s one of the ideas that made me want to start this whole project in the first place. It wasn’t until I began writing that I realized the thing I posted on Twitter before writing today’s Road House essay is today’s Road House essay. / I’m not going to talk about the week I’ve had, or why it’s been so bad, bad enough that as I type this I am home along with my stepson instead of out with my partner and our friends because we were supposed to go to an all-sad-songs karaoke party together and I am too sad for Sad Song Karaoke. It’s not really my story to tell anyway. I’ll tell you what is, though: Road House.

11. This is the value of writing about Road House in this way. It becomes your subject. It becomes your only subject, and the subject you will always have, whatever else happens. You will always have your bad idea, your self, and your Road House.

12. Have I ever been to an actual road house? I’m not sure. None come to mind. I’ve been to plenty of dive bars, and a lot of non-dive-bars and some not-quite-dive bars, many of which are in houses that have been located on roads, and I’ve been to some chain restaurants with music where you’re supposed to throw the peanut shells on the floor in a performance of, maybe, road housery, but I don’t think I’ve ever been to anything you could actually call an outright road house. I mean, I understand a road house is a tavern, inn, or club on a country road in its initial incarnation, like the Inn of the Last Home (shout out to Otik’s Spiced Potatoes), and I feel certain that at least one of Collins’ essays needs to address what makes a road house a road house, but I haven’t read it yet. I would be surprised if I have thought of a question about the movie that he has not (yet).

a. Is it the possibility of witnessing a bar brawl that makes a road house a road house?

b. Does a road house require live music, ideally the Jeff Healey Band?

c. I feel like a road house must at least have beer and a pool table and definitely not call it a billiards table.

d. I’m not even sure if it has to be on a road. A snowmobile trail seems like it’d be fine. Preferable, even.

e. Is the primary feature of a road house that it’s for travelers, not regulars? In this sense is Applebee’s a road house? Can Applebee’s be a road house? I’ve definitely been closer to witnessing or possibly instigating an actual bar brawl at Applebee’s than anywhere else.

f. the only actual Road House in Tucson is a brew-and-view movie theater. I wonder if they ever show Road House? Perhaps they will when the remake (!!) comes out in 2023, and if they do I will endeavor to see it there.

13. The reason I love bad idea essays is not because they seem dumb or bad but that they’re hard. Anyone can write a good idea essay. But only a real pro—or a real fool, and it’s hard to tell which you are when you start one, which is the entirety of the stakes of the bad idea essay—can write a bad idea to its exhaustion/completion. Only after exhausting yourself will you see if it was worth it.

14. Let me say it is always worth it, even if the results don't please you or aren't easy to publish. It's the process that matters.

15. 365 essays about Road House is an idiotic thing, and its idiocy is part of its appeal. I am often moved by iterative projects (like the kind Lawrence Lenhart made a promise to embark on in his Dec 20th advent essay), because in repeating an action every day or every week or every year you make time a subject.

16. Time is always a subject, as well as a tool, but in an iterative essay, time becomes unavoidably a primary subject. How long can Christa Wolf sustain her One Day a Year project (until she died!)? How many comment cards can Joe Wenderoth write and send to Wendy’s? How many nachos of Indiana can Sean Lovelace eat and write about? How many phone calls can Lenhart make and document by the end of the year, and will he survive it? How many letters can Nicole Walker write to Arizona Governor Doug Ducey? (The linked one, Dec 2, 2022, was the last one, if just because Ducey is finally leaving office. Respect to her!)

17. An aside: Have you thought about just how good a deal books of essays and short stories are? I just bought the new Jack Driscoll collection 20 Stories for less than twenty bucks. That’s me getting 20 stories for a dollar each! I get to keep them forever, too.

18. Twenty dollars seems to me like a lot for a novel, however. You only get one novel for that money. You could have got 20 essays. Or, shit, 50 poems!

19. I mean that a good poem or story or essay stays with me more than a good novel does. I know I'm in the minority but that's how I'm built. Maybe I’m just a shitty reader. I’ve been told that before.

20. I am reminded of the time when we were kids that my brother and I each got $50 for Christmas to spend as we liked. Ben took his $50 as one bill. I wanted 50 ones, which I got. 50 felt more substantial than one, even if it was worth the same amount of money. Then we went to Marquette to spend them at American, seemingly the only good store in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. I still think 50 one dollar bills feels better than one 50 dollar bill, especially if you're a kid. But then my brother's an investment banker who lives in a giant house and I write advent essays for free on this website. Maybe there's a lesson in that.

21. The reason I love iterative projects is that the plot is inevitably the movement of the mind (or the life or the body) through time. Every piece is a technical problem: oh shit, what am I going to do today? And the technical problem just gets harder as it goes deeper: How can I not bore myself on essay 241? (I'll have to let you know when I get there, but I feel like Collins is going to be able to solve this problem just fine.)

22. So when I read, say, essay 46, “The Agreement, Part Five: Tableau II” (he returns to many of the core ideas and scenes multiple times from multiple angles), I’m entertained and not a little amazed that we’re talking about the weird, short scene where a bar patron (Sharing Husband) offers to let another bar patron (Gawker/Groper) fondle his wife’s (Well-Endowed Wife's) breasts for $20. And then the guy doesn't even have the money! Even more entertainingly, this is the fifth (of seven I’ve so far encountered) essay on this weird throwaway moment in this weird, possibly throwaway film, and each manages to improbably get at some new aspect of the scene.

23. Possibly if this scene made any real narrative sense in the context of the film or sense at all really it might be less permeable to the mind of the essayist, and because Road House has so many inexplicable scenes like this Road House becomes an ideal cipher.

24. What I really like about essay 46 in particular is how it dead-ends into a set of references that I’ve never really seen anyone make before, and certainly not in this configuration and all at once. I’ll quote the end of the piece to show you:

But for now let’s look at this miserable bastard, transformed by the spectacle of the tripartite Agreement between Sharing Husband, Well-Endowed Wife, and Gawker/Groper from a belligerent cut-up to fucking Saul on the road to Damascus, transfixed by the sight, blinded by the light, revved up like a deuce, another runner in the night, just completely poleaxed by watching one idiot feel up another idiot’s wife. / You don’t see that. You might still see it [I did initially mistype it as tit, amusingly, and felt that was meaningful enough to note —Ander] in the desert—shout out to the Orb—but you don’t see it at Duggan’s, and you don’t see it where Dalton works. Beautiful in its idiocy, the world Tilghman is building has no room for it. The Elves sail West and the Gawker and Heckler and Sharing Husband and Well-Endowed Wife disappear and so help me God the bar as I sit here writing this the bar is playing “I’m Shipping Up to Boston” by Dropkick Murphys and where is Dalton and Thomas Nast when you need them.”

See what I mean? I laughed hard at the Orb reference, cued as I was already by the Blinded by the Light ref, and that they’re exactly 25 years apart adds to the trick, and then when the (Tolkien) Elves show up I’m really here for it, and I just heard that Dropkick Murphys song for the first time only last year, and it’s a hell of a song with its own full commitment to its own bit. I mean that I see the stars in the sky and I can see him connecting them as he goes, and I’m here for the resulting constellation.

25. Any iterative project—any restrictive form like this one is—breaks down at some point in its exercise over time. The pressure of the external form on the huge ever growing pulsating brain that rules from the centre of the ultraworld and the pressure of that brain’s growing internal energy out against the artificial walls of the form: this is a thrilling plot and one I am always here for. I'm really really looking forward to the next couple hundred essays on Road House and to its inevitable breakdown: I hope it's a good one. And I hope I've also got you interested enough by the end of this essay to give these weirdo Road House essays some time. (I'm still not 100% sure if the movie is worth your time or not, but Collins is starting to sway me to yes.)

*

Ander Monson is one of the editors of Essay Daily and the author of Predator: a Memoir, a Movie, an Obsession (Graywolf, 2022), a book not (so far) on any of the year's Best Of lists which he is pretty sure is either an oversight or a category error.

Wednesday, December 21, 2022

Advent 2022, Dec 21, Susan Briante, Our Midwinter Days

Our Midwinter Days

Susan Briante

As I write this, the Christmas lights hung from our eaves strum a flickering tune against a sky the gray of water at the bottom of an old pan. The sun rose into clouds today and blued the Tucson afternoon for a little while, but now the color drains. If you asked me what I did during this sliver of a day, the list feels paltry: I ran on a trail beside the dried riverbed, came home, made a holiday card with my daughter, cooked some chicken with garlic and cannellini beans, threw a load of laundry in the wash, read, made some notes toward this essay. What more could there be to say?

As you read this, we (at least in the Northern Hemisphere) share our first midwinter day without the poet Bernadette Mayer. On December 22, 1978, Mayer made this day hers by writing a 119-page dream-to-morning-to-afternoon-to-evening account of her life as a writer, thinker, mother to two small children, and partner to poet Lewis Warsh. But “account” doesn’t capture the scope of her project. Mayer’s book-length poem Midwinter Day presents a brilliant mind narrating thoughts, memories and observations as she dreams, wakes, feeds children, goes with them (and Warsh) into the cold of Lennox, MA, to return library books and pick up groceries, goes home, reads to children, cooks, and writes. Her words careen and croon in a masterful musicality. Poet Alice Notley has called the work “an epic poem about an ordinary day.”

I was first introduced to Mayer watching her read her poem “Eve of Easter” on the Poetry Project’s Public Access Poetry Channel on You Tube. “Milton,” Mayer begins by addressing the author of Paradise Lost. “I have three babies tonight.” And from there she turns an evening of childcare into a rumination on literary legacy and mothering. (“I stole images from Milton to cure opacous gloom/To render the room an orb beneath this raucous/Moon of March, eclipsed only in daylight/Heavy breathing baby bodies…”) It is extraordinary and tender, and if you haven’t already read or seen it you might want to do so right now for a taste of Mayer’s heart and humor, ear and intellect. Recorded months before Mayer would write Midwinter Day, the black and white video spans 3:07 minutes but seems much longer.

Midwinter Day builds off that same impulse to do more than make do with whatever life gives us, to take a situation like baby sitting and make art from it. Just as Melville, Hawthorne and Milton become Mayer’s companions in childcare in “Eve of Easter,” Catullus, Freud, Hawthorne and Joyce all make appearances in Midwinter Day, where they are joined by movie stars (Ava Gardner, Gregory Peck, and Jane Fonda) as well as friends (poets Clark Coolidge, Ted Berrigan, Notley, among many others); even the Shah of Iran makes several cameos throughout the poem. People come and go in Mayer’s dreams (which open the book) as well as in her memories which wind their way throughout her narration along with observation, literary and local history, psychoanalysis and inventory.

In my memory of first reading Midwinter Day, I sit on a red leather couch bought from a Dallas coffee shop for $100. (It smelled of espresso for months.) I hold Gianna on my lap cradled in one arm, the book in the other. I look up from book or daughter across the six lanes of traffic in front of our house to a splinter of park, dead leaves and black walnut trees. I’m waiting for Farid to come home from his teaching gig at a private high school across town, so I can hand him our child and start working on writing or dinner. That first winter with my daughter, the days felt long (even though the daylight was short), and I felt isolated and overwhelmed by motherhood. But the specificity of that particular moment on the couch feels a little off. Gianna almost never took naps. If she was still, I was probably nursing her, which would have made the book hard to hold. My memory reshapes its banks like a river bound to currents and geographies I barely perceive. Mayer was fascinated with the technologies of recall. In her 1971 project/ installation Memory, she shot a roll of 35 mm film every day for a month and kept a journal. But her proposal for Midwinter Day extended beyond remembrance. She tells us “I had an idea to write a book that would translate the detail of thought from a day to language like a dream transformed to read as it does, everything, a book that would end before it started in time to prove that the day like the dream has everything in it, to do this without remembering….”

As in James Agee’s unwieldy masterpiece Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Midwinter Day teams with unflinching descriptions: of the items crowding a table or closet or hallway, the books that line the shelves of the local bookstore, the businesses, churches and municipal buildings that make up their town. “What an associative way to live this is,” she writes. Mayer doesn’t shy away from registering the struggle of parenting and art making at the fringes of an economy (“sickening holidays, cold rooms running out of money again/ nothing to do but poetry, love letters and babies.”) But rather than register complaint or critique, Mayer seems most intent in keeping herself interested. The action of making sauce for spaghetti stretches across a page but becomes another way to think of writing as she describes “the commas” of the “cheapest small onions” and the “letters of straight pasta.” Summaries of the books she reads to her daughter (Big Dog, Little Dog; The Three Little Pigs; Popped-out-of-the-Fire) give way to ruminations on Sekhmet, the wife of Ptah, or Septimius Felton, a character of Hawthorne’s. Even when her topics remain in the mundane there’s something enlivening (if not enlightening) about witnessing her get it all down and make it worthy of a place on the page (next to Hawthorne, Milton and Melville). There’s something both familiar and refreshing about Mayer’s feat today when we filter our faces and soundtrack our moments to share in a marketplace of attention. More than posing or posting, Mayer recognizes and honors. She acknowledges that her work is a privilege as she imagines “a Latin Sabine or Etruscan mother/ Who didn’t have the time, chance, education or notion/ To write some poetry so I could know/ What she thought about things.”

I try to imagine my mother in 1978 in our split-level house in the New Jersey suburbs, where she could not walk to a store or find accessible public transportation to get anywhere. What would she have written about? A view to the cul-de-sac, the ragged oak tree, crumbling driveway, the Japanese maple, manhole cover, fire hydrant, the long-legged girl who lived in the house on the corner until her parents divorced. For years, it sounded to me like every sentence spoken by the women in my family had a baseline of complaint, a backbeat of worry. Could my mother have written herself into a legacy or history or out of isolation?

In Midwinter Day, Mayer lists all the women who penned what she calls “a secret history:”

Anne Bradstreet and Tsai Wen Gi,

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Alice Notley and me,

Adrienne Rich, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton,

Elinor Wylie, Louise Bogan, Denise Levertov….

The list continues encompassing H.D. and Nikki Giovanni, Murasaki Shikibu and Muriel Rukeyser, Gwendolyn Brooks and Marina Tsvetayeva, among others (including “the saints.”) In its compilation Mayer creates both a genealogy and a community.

On December 22, 2018, in honor of the 40th anniversary of Midwinter Day, I joined a group of 32 other poets who wrote our day into sections (Dreams, Morning, Noontime, Afternoon, Evening, and Night) on a shared Google doc. I wrote while I hosted family from France, drove 7 hours to California and mourned the first Christmas I would spend without my father. The book Midwinter Constellations collects all our entries and publishes them without individual attribution. When I read back through it, I feel the beauty of forgetting for minute which voice is mine in a chorus of the quotidian.

On November 22, the day that Bernadette Mayer died, I dreamt the moon had fallen from the sky. When I woke the moon was still there. Today, less than a month later, we sit on the dark side of the year, maybe late in the day and perhaps late in our lives. My mother has been gone since 2014.

When I wake today at 6:30 in the midwinter darkness, the Christmas lights continue their flickering, little flashing beads, a rosary for our eyes: light and dark, day and night, paper and ink. The sun’s a little mother who warms and feeds and allows us to see what is right in front of us.

In these December days we feel our scarcity. But that’s just what the myth of American individualism and the treadmill of capitalism wants us to feel. (For more on this, listen to Alexis Pauline Gumbs). It keeps us working. It keeps us scared. A poet like Mayer shows otherwise. Much remains even at the end of the season, at the end of a year, even at the end of a life. Today in places like New York and Los Angeles, online and in Amsterdam, poets will gather to read Midwinter Day in honor of Mayer. On this darkest day, we need to believe that the sun will return, that the children will eventually fall asleep, there will be another hour to write and so much more to be said, that there’s a reader who will follow us to the next page.

*

Susan Briante is the author of Defacing the Monument (Noemi Press 2020), essays on immigration, archives, aesthetics and the state, winner of the Poetry Foundation’s Pegasus Award for Poetry Criticism in 2021. She is a professor of English in the creative writing program at the University of Arizona. Briante is also the author of three books of poetry: Pioneers in the Study of Motion, Utopia Minus, and The Market Wonders.

Tuesday, December 20, 2022

Advent 2022, Dec 20, Lawrence Lenhart, Toward an Unregulated Confessionalism: Prolegomenon to The Calling Party

| With this sentence, I start a new essay. | Its concept is twelve years in the making. |

|

Starting January 1, 2023, I will begin calling everyone in my phonebook. That's 431 calls total, or 1.18 per day for a year. |

||

I am wary of this text [already] because it isn't mine. (Replace "text" with "life.") |

||

How to begin writing a text for which I won't be the author? I stall by calling forth this prolegomenon. |

My first false start was at a bonfire in 2015. I swiped through the digital rolodex as if it was a roulette wheel, and it landed on RM. I sputtered a bit before he hung up. Where I meant to break the seal, instead I soldered it shut. |

|

"Each act of reading the 'text' is a preface to the next. The reading of a self-professed preface is no exception to this rule" (Spivak xii). Might someone, somewhere already be rereading the book I have not even begun writing? |

||

The database is especially full of area codes in PA, OH, DE, AZ, and CA. My main milieus, strange avenues. |

||

This essay is no one's. Instead, "the text belongs to language, not to the sovereign and generating author" (Spivak, lxxiv). |

I will call everyone, no exceptions: my best friend from the old neighborhood in Southwestern Pennsylvania; my old boss/lifeguard captain in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware; whoever picks up at the Buffalo Wild Wings in Akron, Ohio; my ex-fiancée's mom in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina; my estranged and incarcerated cousin in Huntsville, Alabama; my son's best friend's mom's best friend in Flagstaff, Arizona. | |

| I will likely call you too. |

Epistemologically, the blind spot is where I wonder what you know about the frequency of my voice or the swirl of hair on the back of my head. It is what you whisper about me when I leave the room, the state, this relationship.

| How about a new slur for millennials? Now they call us Generation Mute. An article by Alex Jeffries begins, “Ring, ring! Who’s there? If you’re a millennial, you have no idea.” Studies report that seventy-five percent of millennials screen their calls due to apprehension anxiety. | Most contacts in my phonebook are millennials, meaning perhaps I’ll only reach 153 of you —at least initially. I will call back. I will get through. | |

Starting January 1, 2023, I will begin calling everyone in my phonebook. That's 431 calls total, or 1.18 per day for a year. |

||

I probably have “telephonophobia” too but have irreversibly committed myself to this dare |

, a self-administered immersion therapy. |

|

“I do not care so much what I am to others as I care what I am to myself” (Montaigne). But what if we are made through others? |

I am calling…

|

|

In “Son,” Forrest Gander writes, “I gave my life to strangers; I kept it from the ones I love.” |

—The project as I thought it would be:an anthology of the voices of Indian women.. . .—The project as I wrote it: a tilted plane.

| You think; therefore, I am. | I am building a new kind of answering machine. (This is not about posterity.) | |

What then to do with the data of 431 phone calls? I will use a call recorder (Rev), transcription service (otter.ai), data analytics software (Dedoose), word processor (MS Word), and digital sound workstation (GarageBand) to create an audio-biography, a composite anti-memoir in the second-person comprised of my concatenated acquaintances. |

||

Derrida’s différance indicates both difference in and deferral of meaning. |

||

Through différance, “meaning is disseminated across the text and can be found only in traces, in the unending chain of signification” (Mambrol). |

The Calling Party is a collective heterobiography that signals the death of compartmentalization. A fuzzy feedback arena. |

|

One may choose to listen by area code/milieu. Or filter by theme. To hear all responses to, “What would be a fitting way for me to die?” in succession, by toggling to Q13. There’s a randomizer too that produces a new text each time it is refreshed, resulting in a collage of sound bites. When I press that button on January 1, 2024, the resulting text will be the basis for the official codex for The Calling Party. |

Lawrence Lenhart is the author of The Well-Stocked and Gilded Cage (Outpost19), Backvalley Ferrets: A Rewilding of the Colorado Plateau (UGA: Crux), and Of No Ground: Small Island/Big Ocean Contingencies (WVU: In Place). With William Cordeiro, he wrote Experimental Writing: A Writer's Guide and Anthology (Bloomsbury, forthcoming). His prose appears in journals like Creative Nonfiction, Fourth Genre, Gulf Coast, Passages North, and Prairie Schooner. He is Associate Chair of English at Northern Arizona University and Executive Director of the Northern Arizona Book Festival.

Monday, December 19, 2022

Advent 2022, Dec 19, Nicole Walker, TikTok Manifestations by Non-Boomer, Non-Gen Z specimens: A Gen-X approach.

Maxwell Sather (Gen Z), Zoe Sather (Gen Z), Nicole Walker (Gen X)

*

Abstract: TikTok is a media platform devoted primarily to social media users age 10 to 20. These users appreciate and are able to digest short-form films delivered to these adopters in 15, 30, and 60 second intervals. TikTok uses algorithms similar to older models of social media such as Twitter and Facebook. As the user ‘likes’ (by pressing an electronic button shaped as a heart) a video, follows a particular TikTokker, or searches for content by category, the algorithm then ‘pushes’ content that the user will fine diverting, amusing, or distracting. There is some evidence that how long one lingers on a TikTok video contributes to the algorithmic calculations but to an independent observer, this is difficult to verifier. Because a considerable number of TikTokkers are comprised of the Generation “Z”, our work here is to determine whether it is possible for a person of the Generation “X” to develop a TikTok strategy, or, algorithms willing, a following, without be called a “Boomer” by other participants.

Keywords: Tik. Tok. Upload. Seconds. Chicken.

Introduction

In an effort to promote Walker et al’s essay collection Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster, which was released in March 2021 in the middle of a pandemic, Walker undertook an unconventional approach. While promotional plans had including serving charcuterie at various book-selling events, Covid 19 et al., prohibited the leaving of house, the sharing of food, and the selling of books. In 2022, Walker endeavored to produce several short videos and upload them to a new social media platform with the help of Sather et al. whose experience, attention span, and training prepared them especially for this work.

Methods

Study Design: TikTok was selected as the platform for a dyad of reasons. 1. Subscribers to older model social media conglomerates like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram had been previously inundated with attempts by Walker et al to entice them to read her collection, contaminating those platforms. 2. TikTok affords its users a companionable hashtag system, where different “tiks” can be sorted by “toks.” Thus, #Booktok proved the fecund yet unsullied ground by which we could conduct our experiment.

Sather et al’s paternal parent is a filmmaker which is distinctly not the kind of video Walker intended to produce. Sather et al had both made TikToks with varying degrees of “likes” or “followers,” making them the ideal cinematographers for this study. Materials used included an iPhone 11, a frying pan, a refrigerator, boneless, skinless, chicken thighs, bacon, square-shaped Tupperware, and a copy of Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster. While each videos strategies differed slightly, we adopted the ‘common’ form of video collecting, pointing the camera at the subject and engaging the ‘record’ electronic button.

In preparation for the procedure, Walker first decided what would cook for dinner. Second, she found a passage in Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster (the title of send book she has currently converted to Macro FN 32) that paralleled that particular meal.

Limited resources, in both imagination and product, constrained the choice of specimen primarily to chicken. Cinematographer Sather positioned the camera implement of his handheld device toward Walker as she unwrapped boneless, skinless chicken thighs from the Foster Farms cage-free brand of chicken. In an attempt to preserve the integrity of the process, chickens raised in crowded but uncaged growth vessels determined our purchasing options. Once the chicken has been removed from the packaging and placed between layers of parchment paper, concern for the welfare of the chicken no longer limited the parameters of the experiment. In order for the chicken thighs to ‘cook’ evenly, thighs must be pounded flat. Sather et al recorded the flattening by aiming the camera implement from the handheld device toward Walker’s cutting board and rolling pin, thereby recording the process of pounding the meat into squares. Walker then laid the chicken thighs in an admixture of flour, paprika, celery salt, and garlic powder, covering both sides evenly, then lying flat in a beaten egg preparation, then again laid into bread crumb coating, designated “Panko.”

Here, the visual recording was halted and the audio recording commenced. Sather et al attempted to instruct Walker on the technological steps to implement an audio recording but gave up and recorded Walker as Walker read Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster:

I laid the chicken between wax paper and got out the rolling pin.

“Where’s the pizza?” she asked. She was used to rolling out pizza dough with me.

I showed her the chicken thighs and pointed out how fat and uneven they were.

“We’ve got to pound them thin,” I told her. “For chicken tenders, they need to be half an inch thick. Do you want to try?” She said yes but she hit the thighs with no force at all. “You have to hit them hard.” I took the rolling pin from her and gave them a whack. They submitted, flattening out, becoming more dough than flesh.

In the middle of the next swing, Zoë yelled for me to stop. “That hurts the chicken.”

I understood her point. It was an odd thing to do: take these round thighs and make them flat. Chickens, factory-farmed grow so fat and thick, the chickens can’t walk. It’s ridiculous, I thought, as I continued to pound the yellow flesh into smooth medallions, that the chicken-growers spent so much time, energy, and DNA manipulation making their chickens grow unnaturally fat and here I am, just thinning them out again. But that’s the only way I knew how to make chicken tenders.

This procedure began as with Experiment one, with the packaging of the specimen: Walker unwrapping butter as she prepared potatoes for Thanksgiving. Given time limitations, Sather et al. cooked, read, promoted Macro FN 32 and conducted recordings simultaneously. It should be noted the Joel Robuchon suggests one pound of butter for two pounds of potatoes but not even Walker has been able to repeat this experiment without severe damage to both the lab, the specimen, and the personnel. However, these potatoes, peeled, quarter pound buttered, quarter cup milked, and whipped in the culinary centrifuge, turned out as expected: buttery but not disastrously so. The results of the promotional aspect of the experiment are less certain.

Results:

For the third experiment, due again to time limitations and the labile conditions of the specimen, Sather et al recorded cleaning the refrigerator instead of focusing on a singular aspect of a specimen such as chicken or butter as in experiment one and two. The cinematographer recorded Walker removing squares of Tupperware, petri dishes of microorganisms, and hazardous biologic material from the specimen for a 30 second interval and then recorded restocking the specimen with material inoculated with spores and microbes in conditions not yet catalyzed for spontaneous growth.

Walker, still restricted in audio capacity, required Sather et all to adjust the technology for Walker to read from Macro FN 32:

I spill applesauce down my shirt while trying to shape it into something palatable for Zoë. This little baby will not eat. Or, she won’t eat anything as perimeter-defying as applesauce. She will not eat anything that isn’t square, so I’m always sticking macaroni and cheese into the refrigerator in a Rubbermaid container. When it’s cold and hardened, I pop it out of the plastic and cut the newly formed mass into squares. Everything must be made square—because she likes the pointy edges or because I am limited to squares by my sculpting skills, I’m not sure. Mashed potatoes I take between my hands, pat into a square, and fry. Cucumbers, cut down the middle, edged, and quartered, she’ll eat. It looks strangest on the meats—chicken squares, steak squares. I try to resist taking her to Wendy’s daily for the pre-squared hamburgers. If you take the tops and bottoms off Wendy’s fries, they are practically Pythagorean.

Because the specimen chicken has been well-studied herein and bone-in chicken may disturb our reader, the editors request Experiment four only be charted and cited. However, please note, Sather et al. coats the chicken in paprika, celery salt, and garlic powder in the data-collection.

There is chicken on the bone. There is chicken off the bone. Chicken on the bone is the chicken I’d want in all its decadent renderings—by all I mean one. Fried chicken. There are many bone-in chicken recipes like chicken hindquarters in port and cream, barbecued chicken, buffalo wings, though they may be a kind of fried. But fried chicken is a testament to the beauty of the disarticulated chicken. Every piece a handhold. Every piece its own integrity. The coating wraps a thigh like snow, a breast like a scarf, a leg like a stocking to protect it from the cruel world of hot oil. Frying chicken is the nicest thing you can do to a dead chicken.

But there are some who cannot eat the chicken on the bone. Breast of chicken, boneless thighs, cubed in korma, rolled cordon bleu, that’s doable. At the bar, spicy drummette in my right hand, hot sauce on my cheek, a pile of bones in front of me, I turn to my friend Ander, who will not eat the boney chicken but is currently eating chicken tenders. I do not comprehend his reluctance.

“It’s the same thing,” I argue.

“It’s not.” He pushes my plate of sticky bones further away.

“But you eat meat. Chicken. Steak,” I say.

“I prefer hamburger,” he says.

Perhaps he does not like the resistance of muscle.

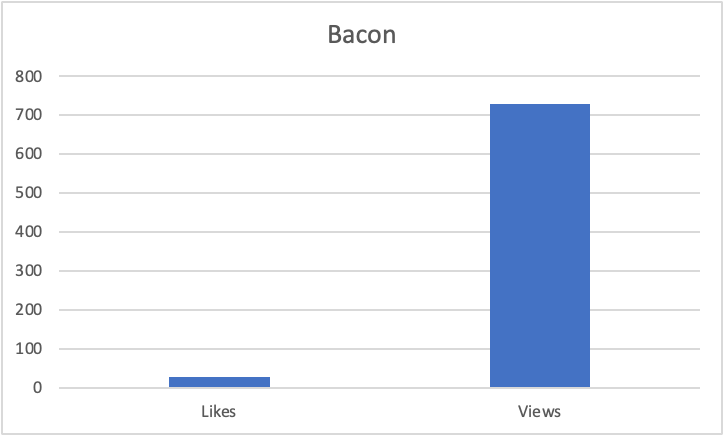

A final experiment, henceforth referred to as Experiment five, produced outlying results. While the primary visual record is of the specimen frying in a pan, inferences may be made that specimen bacon, while equally subjected to unseemly living and death situations, is easier to render digestible because of its exuberant effect on the tastebuds, even as perceived through a visual medium. The data here thus outlie our previous experiments but are noted for significance. Please note that while the inputs trend higher, the ratio remains the same. Sather et al include these data for reference only.

During the H1N1 pandemic scare, I start stockpiling groceries. I buy twelve cans of Cento tomatoes, twenty boxes of spaghetti. It’s not as if I think the grocery stores are going to close tomorrow. But I should start preparing—part as pure logic and part as an offering to the gods of swine flu. I buy two pork tenderloins, two pounds of bacon, and a saver-pak of pork chops. A little protein in the form of cheese won’t save me but a lot of pig might. I’ll fight fire with fire. I’ll develop my own antibodies to the H1N1 out of bacon. I realize that it’s not the pig that will kill me, but, lacking any other sort of game plan, I reason that pig is a prophylactic. I will eat him homeopathically.

In conclusion, it shall be inferred that TikTok, while a forum designed for a generation well-practiced in giving short-term attention and incessant dopamine infusions, other generations may learn to adapt and avoid being called “Boomers” if collaboration with the generation Z may be forced. However, we must conclude that becoming a TikTok sensation is not likely. These experiments must be repeated for results to prove valid. Future study is indicated in the specimens of pomegranate, beef tongue, and beef Jell-o. The larger conclusions may be even less promising. Self-promotion is an embarrassing sport and the promise of finding book readers in a TikTok world is ever shrinking. And yet, the show must go on.

Notes: Walker neglected to push “post” on Experiment one so Experiment one should now be imagined as Experiment five. Walker also included two additional hashtags: #food and #chickentenders which garnered, we believe, more views. It also drew three comments: “Is this a book? It seems like a book.” And “Thanks for the dating advice, coach” and “This seems like an audiobook.” And “You should write a book.” These comments seem linked to the fact that Walker neglected to record an image of Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh, and Navigating Disaster. Walker’s Macro usage has been suspended until further investigations can be conducted.

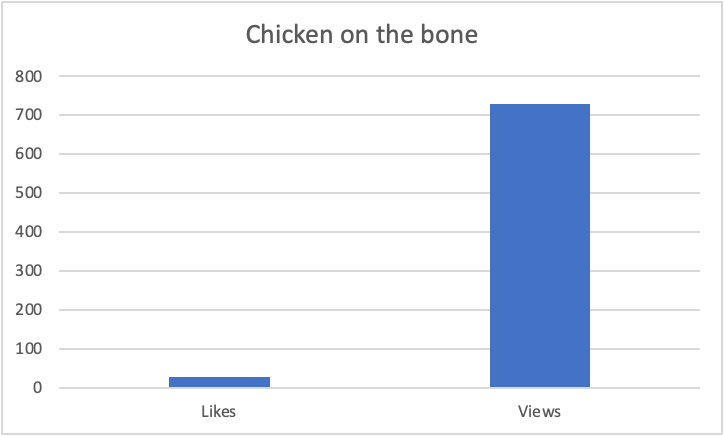

Chart for Experiment One updated as of 12/17/2022, 11:05 a.m.:

*

NICOLE WALKER is the author of Processed Meats: Essays on Food, Flesh and Navigating Disaster, (AKA Macro 32) The After-Normal: Brief, Alphabetical Essays on a Changing Planet, Sustainability: A Love Story, Where the Tiny Things Are, Egg, Micrograms, and Quench Your Thirst with Salt. You can find her at https://www.facebook.com/nicole.walker.18041 Twitter: @nikwalkotter and website: nikwalk.com and TikTok @nicolewalker263

Sunday, December 18, 2022

Advent 2022, Dec 18, Julie Lunde, 100 Essayistic

x3 – 6x2 + 11x – 6 = 2x – 2

Fuck math, I’m an essayist.

I love math, but I haven’t done it in years, I’m an essayist.

“To know x = to know (everything – x).” [i]

“The limit does not exist!” [ii]

There was a math teacher at my high school, I forget his name, who was married to the history teacher—I forget hers, too. They always held hands in the hallways. He was rumored to teach in hyper-speed so he’d have two whole weeks free at the end of the schoolyear to tell his students the story of how they’d met; apparently, it was The Greatest Love Story Of All Time. But his students were sworn to secrecy, and I never took his class…

Let ‘x’ be a real number.

The first game of ‘ultimate,’ also called ultimate frisbee, took place in a parking lot at Columbia High School in New Jersey, in 1968. The sport was the casual after-school creation of a group of friends, but its appeal proved contagious; an alumnus of CHS got his hands on a copy of the rules and founded an ultimate team at Staples High School in Connecticut in 1970, and before long, there was a CT league, and from there the trend went national.

“100. It often happens that we count our days as if the act of measurement made us some kind of promise. But really this is like hoisting a harness onto an invisible horse…” [iii]

This looks just like math homework—like a sheet of word problems.

100. Let ‘x’ be a real number. If x3 – 6x2 + 11x – 6 = 2x – 2, solve for x.

An essay, from the French essai, is an attempt. It isn’t an answering, but a mind at work.

You got 24-Down wrong. The first letter is ‘S’.

There’s no wrong answer when it comes to writing something new, something original, an essay that is yours.

There can be multiple correct answers (in writing). Multiple factors go into it (writing beautiful essays).

I’m teaching you guys the highest level of math I know! Think about that—you’re only what, seventeen, and one day soon you’ll know more advanced maths than I do now! By the time you’re my age—and I’m not that old—think how much more advanced you’ll all be!

Instead, she studied how to become an essayist.

“In my Pre-Calculus class last year, when Mr. Wetzel was asked, “When are we ever going to use logs (logarithms)?” He wisely replied, ‘In a fire.’” [iv]

“One must be able to say at all times—instead of points, straight lines, and planes—tables, chairs, and beer mugs.”

I want to show you, show myself, how math is essayistic—how essays are math, or mathematical. I’m trying to examine how that overlap works.

“Last Wednesday, Al Jolley, Staples math teacher and frisbee coach, was seriously injured when he attempted to make the famed “oral grab” (trying to catch a frisbee in his mouth). Suffering a broken jaw and loss of three teeth, Jolley commented, “shirpvgmn….’” [v]

Suppose that among four consecutive numbers, the product of the first three equals twice the third. What’s the fourth number? [vi]

“All players are responsible for administering and adhering to the rules. Ultimate relies upon a Spirit of the Game which places the responsibility for fair play on every player. Highly competitive play is encouraged, but should never sacrifice the mutual respect between players, adherence to the agreed-upon rules of the game, or the basic joy of play.” [vii]

Group like terms on one side: x3 – 6x2 + 9x – 4 = 0.

Rewrite to seek out commonality: x3 – x2 – 5x2 + 5x + 4x – 4 = 0.

Take a look at this solver’s organization, the elegance of expression, their creativity in seeking out the solution this way….

To show; put to the test; inspect.

Factor: x2(x – 1) –5x(x – 1) + 4(x – 1) = 0.

Factor: (x2–5x + 4) (x – 1) = 0.

Factor: (x – 4) (x – 1) (x – 1) = 0.

x = 1, or x = 4.

Julie Lunde has an MFA in nonfiction from the University of Arizona. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Western Humanities Review, Pigeon Pages, and the anthology Letter to A Stranger: Essays to the Ones Who Haunt Us (Algonquin, 2022) among other places. She serves as an assistant nonfiction editor at DIAGRAM and is the writer in residence at her dog's house. See more at julielunde.com.